Queensland researchers have identified a domino effect from a brain stimulation technique used to treat psychiatric disorders such as clinical depression.

The University of Queensland and QIMR Berghofer scientists have found that transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) can alter activity beyond the stimulated region and throughout the connected networks of the brain.

Transcranial magnetic stimulation of the brain

UQ Queensland Brain Institute researcher Professor Jason Mattingley said TMS was a non-invasive procedure using magnetic fields to stimulate nerve cells in the brain.

“It is sometimes used to treat depression, when medications haven’t been effective,” he said.

The latest research findings may shed light on how to use TMS in a more targeted way to treat mental health disorders.

“As well as a research tool, TMS is becoming more widely accepted as a clinical treatment for neurological and psychiatric disorders, but it’s been unclear why it is effective,” Professor Mattingley said.

“As a proof of principle, our work focused on two visual brain areas – one that registers basic sensory information, and another that regulates what we do with that information.

“Stimulation of the sensory area increased functional connections with other brain regions, whereas stimulation of the regulating area actually decreased the interactions.

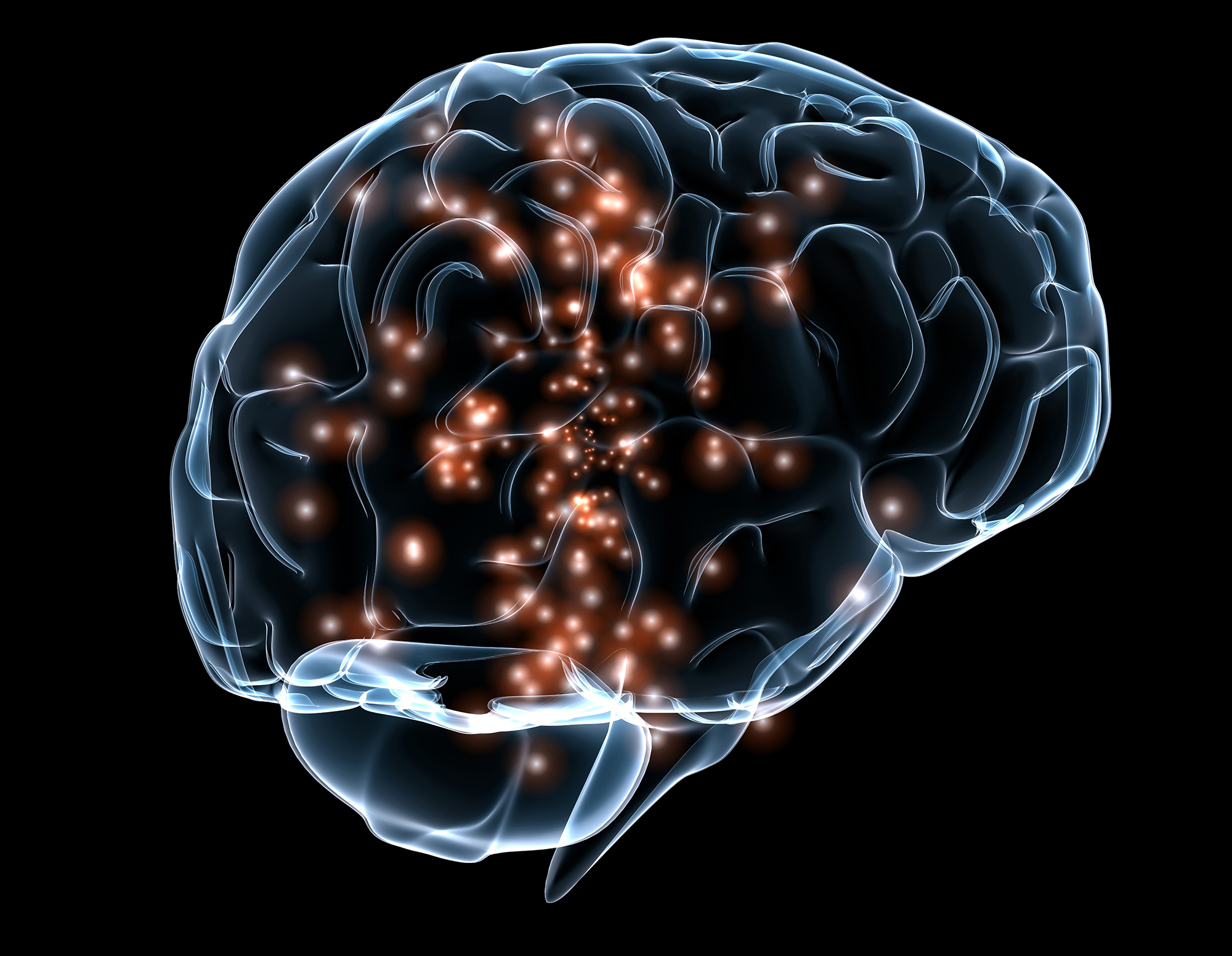

Understanding networks of brain wiring

QIMR Berghofer’s Dr Luca Cocchi, who led the study, said it was helpful to understand the role of the networks that wired the brain together.

“This work shows us that when TMS is applied to one area of the brain, it selectively alters communication between distant brain regions, depending on where and how we apply it,” Dr Cocchi said.

The researchers also used computational modelling to establish the biological mechanisms responsible for the TMS effects.

“We now think TMS alters communication between distant brain areas by changing the timing of local neural operations,” Dr Cocchi said.

“If TMS causes the stimulated brain area to run more slowly than usual, then this shift in activity has a knock-on effect for how it interacts with other brain areas.”

The research, published in eLIFE, was funded by the Australian Research Council, the National Health and Medical Research Council and UQ.

Media: QBI Communications, communications@qbi.uq.edu.au.