A new form of secret light communication used by marine animals has been discovered by researchers from the Queensland Brain Institute at The University of Queensland.

The findings may have applications in satellite remote sensing, biomedical imaging, cancer detection, and computer data storage.

Dr Yakir Gagnon, Professor Justin Marshall and colleagues previously showed that mantis shrimp (Gonodactylaceus falcatus) can reflect and detect circular polarising light, an ability extremely rare in nature. Until now, no-one has known what they use it for.

The new study shows the shrimp use circular polarisation as a means to covertly advertise their presence to aggressive competitors.

“In birds, colour is what we’re familiar with and in the ocean, reef fish display with colour – this is a form of communication we understand. What we’re now discovering is there’s a completely new language of communication,” said Professor Marshall.

Linear polarised light is seen only in one plane, whereas circular polarised light travels in a spiral – clockwise or anti-clockwise – direction. Humans cannot perceive polarised light without the help of special lenses, often found in sunglasses.

Circular polarised light a form of secret communication

"We've determined that a mantis shrimp displays circular polarised patterns on its body, particularly on its legs, head and heavily armoured tail," he said. "These are the regions most visible when it curls up during conflict."

“These shrimps live in holes in the reef,” said Professor Marshall. “They like to hide away; they’re secretive and don’t like to be in the open.”

They are also “very violent”, Professor Marshall adds. “They’re nasty animals. They’re called mantis shrimps because they have a pair of legs at the front used to catch their prey, but 40 times faster than the preying mantis. They can pack a punch like a .22 calibre bullet and can break aquarium glass. Other mantis shrimp know this and are very cautious on the reef.”

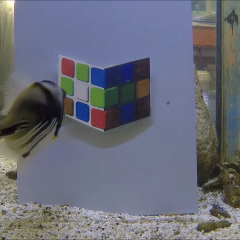

Researchers dropped a mantis shrimp into a tank with two burrows to hide in: one reflecting unpolarised light and the other, circular polarised light. The shrimps chose the unpolarised burrow 68 per cent of the time – suggesting the circular polarised burrow was perceived as being occupied by another mantis shrimp.

“If you essentially label holes with circular polarising light, by shining circular polarising light out of them, shrimps won’t go near it,” said Professor Marshall. “They know – or they think they know – there’s another shrimp there.

Secret light communication may help cancer detection

The findings may help doctors to better detect cancer. “Cancerous cells do not reflect polarised light, in particular circular polarising light, in the same way as healthy cells,” said Professor Marshall. Cameras equipped with circular polarising sensors may detect cancer cells long before the human eye can see them.

Another study involving Professor Marshall, published in the same edition of Current Biology, showed that linear polarised light is used as a form of communication by fiddler crabs.

Crabs use polarised light to communicate too

Fiddler crabs (Uca stenodactylus) live on mudflats, a very reflective environment, and they behave differently depending on the amount of polarisation reflected by objects, the researchers found.

“It appears that fiddler crabs have evolved inbuilt sunglasses, in the same way as we use polarising sunglasses to reduce glare,” Professor Marshall said.

The crabs were able to detect and identify ground-base objects base on how much polarised light was reflected. They either moved forward in a mating stance, or retreated back into their holes, at varying speeds.

“These animals are dealing in a currency of polarisation that is completely invisible to humans,” Professor Marshall said. “It’s all part of this new story on the language of polarisation.”

Both the mantis shrimp study and the fiddler crab study are available online in the journal Current Biology.

Media: communications@qbi.uq.edu.au